We are in a transitional part of the year. It is about now that industry observers are hoping to see the first green shoots of post-pandemic demand. Yet we may be emerging into a different landscape: and we’ve seen more voices making predictions for what supply chains will look like, and where global production will be based, following a post-pandemic reset.

Some claim that international trade tensions and lessons from the pandemic mark the end of globalisation as we know it, while others are anticipating a good year for air cargo now that the Chinese Mainland has reopened and pent-up manufacturing demand can be released. As ever, the truth probably lies somewhere in between.

Cathay Cargo GM Cargo Commercial George Edmunds points out the first and obvious benefit of China lifting its pandemic restrictions. ‘The overall situation is clearly much better when the Chinese Mainland is open,’ he says. ‘There is now a more settled economic environment there, which we think will be conducive to increasing confidence in supply chains.’

Chinese Mainland network up and running

Cathay Pacific is now operating a nearer-to-normal passenger and freighter operation to the Chinese Mainland. Capacity is only set to grow as Cathay Pacific restores its network, with 50 per cent of its pre-pandemic passenger capacity online by the end of March.

Yet consumer demand remains slightly muted, and there is definite sense across the air cargo industry that shippers are spreading risk across their supply chains so they are not as dependent as they were on the Chinese Mainland, which implemented some of the strictest anti-pandemic policies and for the longest duration. These affected Apple’s export plans for its flagship iPhone 14, and there are many reports that the tech giant is looking to move around 25 per cent of its iPhone 14 manufacturing from the Chinese Mainland to India by 2025 to mitigate against future risk.

‘I think everyone has looked at their risk profile in more detail as a result of COVID-19 and they probably now have a greater appreciation that while you might be confident in something, you should always have a back-up plan,’ adds Edmunds. ‘We recognise that people will be building a bit more into their supply chains to ensure that they can be more confident, and the “China+1” model is becoming clear. This is something that many people are considering, with Apple probably being the best example of it.’

Near- and friend-shoring supply chain models

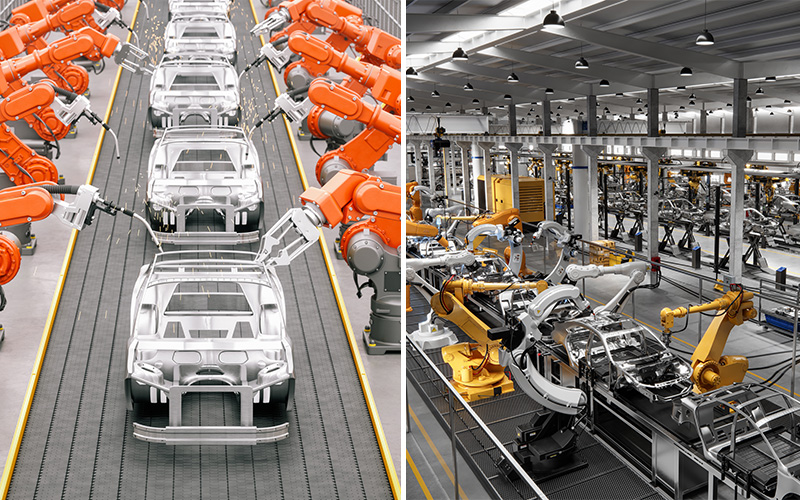

This fits with another related idea: near- or friend-shoring. This involves shortening or redesigning supply chains to keep manufacturing inventory close to, or between, territories with stable geopolitical relations, or by diversifying production sites. India, Vietnam and other South East Asian countries are frequently mentioned in this regard. So is Mexico, thanks to the US auto industry’s increasing move towards electric vehicles.

‘EVs in the US are coming more and more from Mexico,’ says Christopher Clague, Senior Editor at Flexport Research, which is part of the Flexport freight-forwarding group. ‘Ford’s Mach-E SUV plant came online in 2020. Nissan has an EV factory there as well, while Tesla, Volkswagen and BMW all have EV plants planned and the shovels have already hit the dirt for some of them. And you’re seeing a lot of Chinese Mainland auto-parts manufacturers start to invest in Mexico because they see this coming too.’

Vietnam and South East Asian ‘+1s’

But upping sticks and moving existing manufacturing is not a process for the faint-hearted when you consider the infrastructure costs, and the matter of finding or training a highly skilled workforce. And while Vietnam, for example, has seen exports to the US increase by about 15 per cent between 2018 and 2021, there are complications in moving there. Inward investment is welcomed but there are limits and conditions, and the country’s logistics infrastructure needs a lot of investment to increase capacity. It’s receiving it – including around US$17.6bn being injected into the country’s airports by 2030, essential if premium manufacturing is to relocate with the intensity some are predicting.

Yet Clague points to an actual decline in US nominal imports from Vietnam towards to the end of last year. ‘Vietnam is one of the big “China+1” stories,’ he says, ‘but it’s not showing up in the top-line data yet.’

Globalisation is still in play

So while there may be a sense that shippers are diversifying supply chains, it will probably not be the immediate process some of the more urgent voices suggest. This is backed up by the most recent DHL Globalisation Index. ‘The latest numbers may surprise some readers,’ it states. ‘They clearly show that international flows have been remarkably robust in the face of today’s headwinds, strongly refuting the notion that globalisation is on the retreat.’

It is, of course, hard to get an accurate gauge because there are other factors at play too. Inflation has dented consumer confidence in many territories, and both wholesale and retail inventory levels still remain high. In the US, they are 15 and 20 per cent up against 2019 respectively, and it’s only later this year that they might start to clear. ‘As long as these inventory levels stay high, it’s going to depress demand for imports,’ says Clague.

Linked to that, there are different types of consumers and different types of goods. Vietnam does not yet have the capacity for top-tier, high-end consumer products in significant quantity, and there is some evidence that US inventories remain overstocked with less premium goods.

‘The changing nature of demand during the pandemic was for goods that are mostly not produced domestically in the US, so retailers had to import more,’ adds Clague. ‘And importing requires obviously longer lead times. If you misjudged demand then you’re left with accumulating inventories.’

How is consumer sentiment for 2023?

But what is the current consumer demand for goods, either premium or second-tier? The University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers points to a decline in sentiment in the US, particularly from lower-income, less-educated and younger consumers in its latest report in March.

There’s also the report from the Federal Reserve in February, that credit card debt levels have hit the highest they’ve ever been in the US. If it were to emerge that this debt is fuelled by people at the lower end of the income scale, and who are accumulating debt as pandemic relief packages recede, then there would be a clear cause for concern. ‘I think there are definitely reasons to be cautious about inventories and credit fuelled consumption,’ says Clague.

But he also points to a pretty robust forecast from the World Trade Organisation for this year for trade growth. ‘And the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) just revised up its global forecasts for economic growth this month,’ he adds. ‘There are all these conflicting signals and noise, and it’s hard to pinpoint the single signal.’

Chinese Mainland retains its status

There is one constant, though. The Chinese Mainland’s economy, even under pandemic strictures, has maintained its number one status. The Hong Kong Trade and Development Council (HKTDC) reported that the Chinese Mainland’s imports and exports were up 7.7 per cent in 2022, and the median expected growth for 2023 is five per cent, increasing in following years.

This is good news for Cathay Cargo, and its location at the centre of the Greater Bay Area, with a new connection by sea from the Dongguan Logistics Park. The GBA is an important export hub and a region with a large and more affluent demographic that should also fuel imports.‘While we recognise that much that growth will be driven by internal domestic consumption, it still remains a fantastic base for quality manufacturing,’ says Cathay’s Edmunds. ‘This doesn’t mean that we don’t think that Vietnam has great potential too, but there is still a long way to go for some of these “China+1” destinations.’

Either way, and if the ‘+1’ supply chain reconfiguration does move ahead with more vigour than is currently apparent, Cathay Cargo is in a strong position. ‘While we remain confident about the Chinese Mainland’s future, we’re incredibly well positioned to take advantage of however these flows play out,’ says Edmunds. ‘We can use the strengths of Hong Kong as a hub, and our Merge in Transit initiative, to allow people to bring cargo in from multiple origins across Southeast Asia and China and India, and consolidate in Hong Kong before shipping it on to its final destination.’

It’s positive news from the region as we await the green shoots and for inventory levels to fall.