Preparation is all for Cathay Pacific’s freighter pilots; it’s how they put safety first. While some of the flying is routine, some of the ports they fly to offer real challenges – and a growing number of charter flights can take aircraft to pastures new. Cargo Clan caught up with two captains, also pilot managers, to learn how Cathay Pacific’s flight simulators help prepare pilots for the unexpected, the unlikely and the unknown.

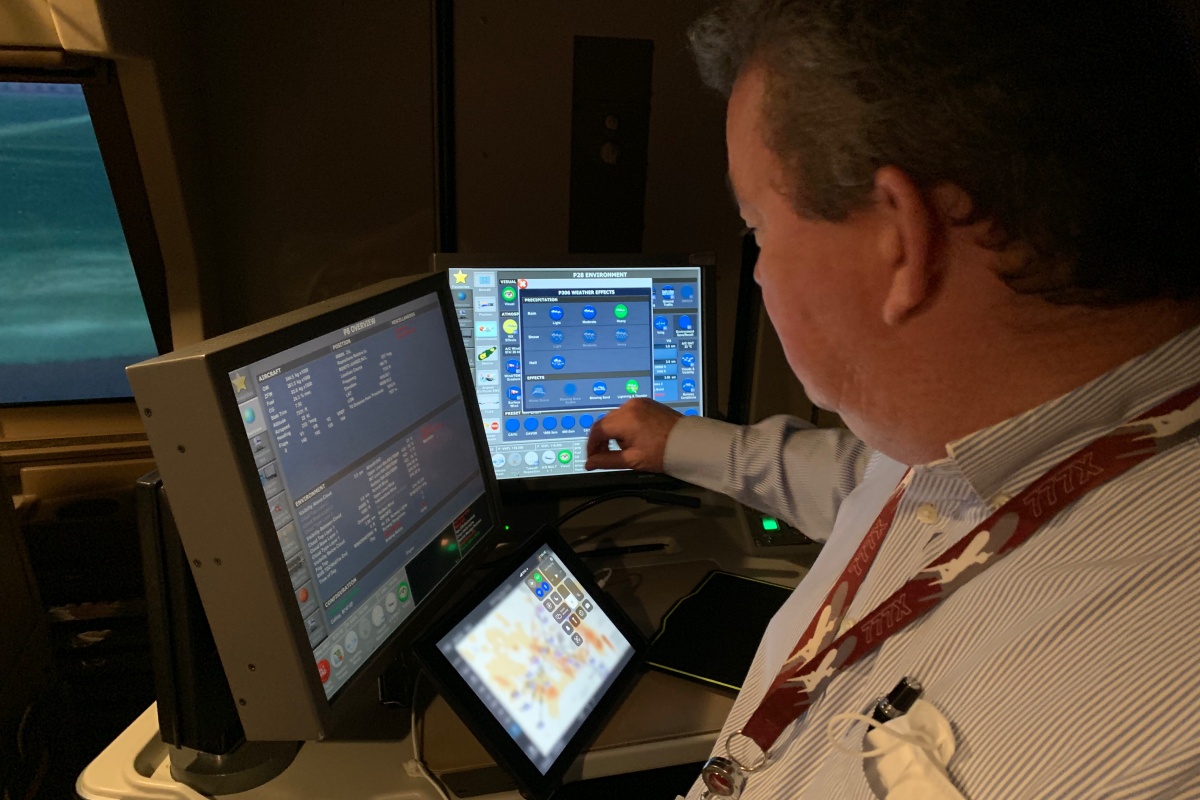

It’s a breezy morning in May, and FOP Risk Manager Pete Hudson and Deputy Chief Pilot (Boeing) Stu Baker are gearing up for a flight in the Boeing 747-8F simulator. Pete will be at the controls flying ‘single pilot ops’, while Stu will orchestrate the weather and other settings from the control panel behind the pilots’ seats. Today, he has promised to limit the engine fires, turbulence and hydraulic failures, which are used to put pilots ‘through the wringer’ for their regular training and licence assessments. ‘It’ll be a comfort cruise,’ he says.

Hot and high

The pilots have chosen Mexico City (MEX) and Hohhot (HET) in Inner Mongolia because they share some characteristics. They’re both at altitude and ringed by higher mountainous terrain and they can both see elevated temperatures, making them prime candidates for ‘hot and high’ flying. This is a challenge for pilots because the higher you are, and/or the warmer it gets, the more air density and oxygen levels reduce. This means you need to go faster relative to the ground to get the same amount of air over the wings to maintain the same air speed.

‘Basically, the plane will fly higher and faster than you would want it to,’ says Stu. ‘We have to tease the aircraft down from what it wants to do.’

We’ll come back to that. For now, although we’re in the simulator hall at Cathay City in Hong Kong, the view out of the flight deck window shows us at the end of runway 23L at MEX, an airport that sits 7,300 feet above sea level. This runway is used for departures by Cathay Pacific’s freighters only five per cent of the time – but that’s why the sim is such a valuable tool. The chances of one of the four engines failing on take-off from this little-used departure is ‘less than 10 to the power of minus eight,’ says Stu. ‘But that’s part of the remit: we train for things that aren’t going to happen.’

Take off from Mexico City

We’re facing southwest. Twenty miles ahead of us, beyond the city’s sprawl, high mountains loom – but even higher terrain, complete with a snow-capped live volcano, lies around to the left. Our departure will take us on a right turn over the city and back over the airport, within the ‘bowl’ of slightly lower hills. The motion is engaged and we’re pushed back into our seats as we start our take-off roll and point for the skies.

After take-off, the city rushes beneath, but thoughts are on the flight path display. A line running left to right shows the angle of our climb over distance – and the mountains approaching quite quickly that we will turn to avoid. ‘We could just clear those peaks with four engines, but we won’t try,’ says Pete. ‘If we lost an engine, our climb gradient would be much lower.’

On three engines, Pete describes this departure as ‘quite a challenge – there are lots of things to contend with’. But on today’s ‘comfort cruise’ Pete has time to point out ‘quite a good golf course down there’ as we follow the track to Guadalajara, the normal route, before we turn off for the start point of our descent back into MEX, on the track the freighters use coming in from Los Angeles and Anchorage. Now we get to see what ‘hot and high’ really means, and which we are compounding with our heavy weight.

The 747-8F has a maximum landing weight of 346 tonnes. Cathay Pacific’s incoming freighters to MEX from the US will weigh around 340 tonnes. It’s a successful route for cargo, and they’re also laden with enough fuel for two sectors – on to Guadalajara and then back to a US port where fuel is cheaper. ‘It’s a trade-off between cost saving and the margins of operating at a high destination while remaining cost-competitive,’ says Pete.

To land or not to land?

On a mild day at sea level, the 747 would ideally have a landing air and ground speed of around 150kts (knots, around 278kph). But at a hot and high airport like MEX, the thinner air means that to maintain an air speed of 150kts, the speed over the ground has to increase to around 210kts (388kph). Stu adds: ‘MEX is the highest threat port on the Cathay Pacific network. The flight data tells us that.’

Why? Well, the approach requires a steeper rate of descent to stick to the glide path, and the aircraft is already going fast. ‘So what we find is that our pilots can experience a bit of a “ground rush” effect,’ says Stu. ‘The ground seems to come up faster, so our pilots tend to flare [the final lift of the nose before touchdown] higher or more aggressively. That means they then “float” down the runway for longer before touchdown. A five-second float at that speed covers much more ground than a 150kts landing at sea level, so we get some late touchdowns and go-arounds when the pilots decide it is safer to try again.’

There’s no shame in this safety-first approach – it’s instilled into pilots. Pete adds: ‘We tell all our pilots that it’s okay to go around if they are concerned about the approach in any way, and at MEX we don’t have much margin.’

Even touching down at the right point takes a lot of energy to bring the plane to a stop in time. ‘The amount of braking energy can be right at the limits of the airplane,’ says Pete.

We’re on final approach, and the runway does indeed seem to be approaching fast. ‘This is the difference between air and ground speed,’ says Pete. ‘I’m doing 173kts but I’m doing 217kts over the ground.’ Just as we hit the perfect position and speed for landing, Pete slams forward the throttles and lifts the nose for a go-around. ‘That would have been right on the money,’ says Stu approvingly, as we climb to a height where they can recalibrate the flight computers and the operating system for a landing in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia.

Touchdown at Hohhot

Each of the two 747 sims costs around US$20m, and a combination of the Rockwell Collins simulator database and imaging from Google Earth offers real fidelity. Stu says: ‘Before our first charter, we’d never been to Hohhot. But we had the capability to go there first in here, because these are incredibly accurate training devices.’

Even though the charter was scheduled to be a day flight, the aim of the sim session was to give pilots an understanding of the terrain near the airport were the flight to arrive at night, for example. Although lower than MEX at 3,500 feet, HET too is surrounded by high terrain in a basin, and the lofty temperatures make it hot and high.

We’re on approach at 9,500 feet, level with the terrain to our left, and the PAPIs (precision approach path indicators) are showing the effects of hot and high. PAPIs are lights set by the touchdown zone on the runway, which form a visual cue to pilots about their position on the glidepath from many miles out. Pilots see four lights – four reds and they’re too low, four whites too high, two of each and they’re on target for an ideal touchdown. ‘We’ve almost got four whites because we’re hot and high,’ says Stu, who has thoughtfully dialled up the ground temperature to 37 degrees from the control panel. But Pete knows exactly what to do, and he brings us in for a textbook landing.

No sooner are the virtual engines cooling than conversation between the pilots turns to what has been learned, and how to further improve the departure from MEX in an emergency. The civilians among us are just left to marvel at the technology – and the flying skills – on show.